SEPTEMBER, 20, 2021

Thomas Talawa Prestø Sets the Stage on Africana Dance

Photos by André Percey Katombe

- words by Ka Man Mak

Edited by Michael Adadek

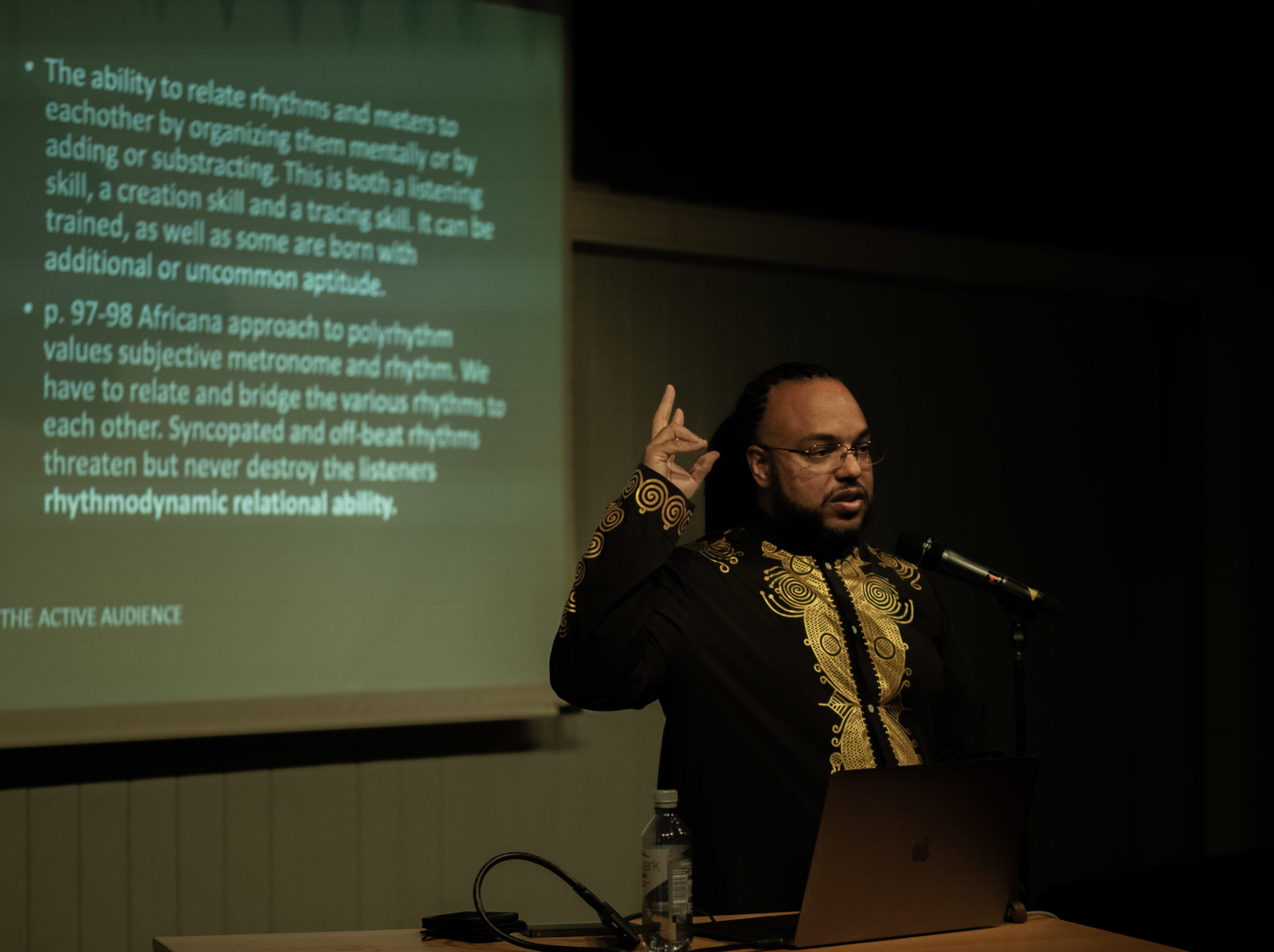

At the Oslo Afro Arts Festival, choreographer, lecturer, founder and

artistic director of Tabanka African and Caribbean Peoples Dance

Ensemble, Thomas Talawa Prestø sets the stage. Imbued in his lecture

was a conscious effort to educate embedded colonial concepts in

academia, philosophy and dance.

“Because this is complex. Extremely complex,” started Thomas Talawa

Prestø charismatically, hopping between Norwegian and English. “And

I acknowledge that.” His slides were deliberately text heavy so that

the audience could take photos and revisit the topic again. “For me,

it has started to become an everyday [sic]. I realised how complex

this was, especially for the Norwegian institutions and when I was

applying for the doctorates. Because I said that my project would

have to be intersectional. It would have to look at the intersection

of gender and race, and also on forced migration and voluntary

migration. The response I got was, “that’s a lot”, you should choose

a few.”

Intersectionality was coined in 1989 by professor Kimberlé Williams

Crenshaw who studies civil rights, race and racism. For her,

intersectionality is used to describe how race, class, gender, and

other individual characteristics intersect with one another and

overlap.

Prestø refused to hem in on the complexity of African art, dance,

philosophy and culture; and oftentimes explained terminologies that

might be unfamiliar to the audience. His lecture visited scholars,

African concepts, dance comparisons and historical events to

illustrate how we are being lied to on a daily basis; and how

African aesthetics should be understood in academia, history, art

and dance.

African dance is parallax

One of his decolonial dance performances, Jazz Ain’t Nothing But

Soul, a collaboration with Dansens Hus and Tabanka, was broadcast

digitally during April to May this year. Jazz, like many dance

forms, has been appropriated by the West, and has roots in Africa.

“We returned to a lot of the art practices which are uniquely

African in its roots. And also translated into the camera as all the

cameras were moving around the dancers. We are continuously dancing

within a sphere, not a circle.”

Using this project, he illustrated how African dance is a parallax,

that “how something looks depends on where you stand in relationship

to it. So, as you change your perspective just a little bit, the

shape and form of it will change. One of the results of having the

audience all around you is that you move your body in a way that is

parallax.”

Africana Dance includes any dance practices, that is contemporary or

altered, from people who are of African descent and carries African

philosophy or thought and culture into their daily practices. This

includes the African diaspora.

“Dancing in the pressure-cooker”

Prestø introduced his doctorate research project, titled ‘Anansi’s

web’. Anansi comes from a West African folktale character where he

takes the shape of a spider, and is considered as a spirit or god

who is a trickster. Anansi is also given the “principle of

communication and storytelling by the God”. The stories about Anansi

became mainstream in the American version, Brer Rabbit and Bugs

Bunny. It is believed that Brer Rabbit stories originated from

enslaved West Africans in America and were appropriated by Joel

Chandler Harris in the 19th century.

Anansi’s web is an artistic research project which engages and

supports Africana dance practitioners in Norway. In particular, the

project looks at “Dancing in the pressure-cooker” which Prestø

coined to describe “dance practices that spring from people in a

pressured situation, such as enslavement, segregation, apartheid,

forced migration, war, homophobia, transphobia and gender

injustice”. One of the goals of the project is to “disrupt the

hegemony of Europeanist theory”.

“Things are not what they seem, especially when you touch on the

diaspora, it is very often not what they seem. All too often when

you do research, the research material is racist, sexist, and is

based a lot on what the researcher recognises. […] It is actually

quite violent to read about it.”

He went further, “Most writings about Caribbean or African-Caribbean

dance started in criminology because the dance was predominantly

spiritual, or spiritually oriented, and so it was illegal to

practise African drumming. […] There is very little neutral material

about the field that I am in.”

Through Western ethnocentric perspectives, it would be difficult to

truly grasp African art and culture, he cautioned.

Prestø used the term, ‘Euro-Western’ instead of western as he sees

himself as a descendent of Africans that are taken forcefully from

Africa to the Caribbean and to the Americas over 500 years ago. He

refused to give away ‘Western’ as though that Africans did not

contribute to it. ‘Western’ is not equivalent to ‘White’ or

‘European’, he explained and admitted that there might be a need for

a better terminology.

The Language That Hides the Brutal Truth

Prestø’s highlighted euphemism used by researchers, such as ‘to

colonise’ hides the brutal violence of the invaders into a country.

He used the indigenous Caribbeans, Taino, as an example that in

their point of view, who are now almost killed off due to

colonisation, would have viewed it as an invasion. “We are already

doing politricks. We are already hiding what we are talking about

and in most incidents, we are talking about war. I have to leave

that clear otherwise it would be indefensible for me to continue.

The Caribbean was a site of war. America was a site of war. South

Africa was a site of war.”

On the screen, he showed two definitions:

Colonalism refers to the historical experience of domination that

coincided with the colonial enterprise, typically traced to the

period between the 18th to 20th centuries.

Coloniality is an epistemic concept that finds its origins in the

15th century discovery of the ‘New World’ which dominates and

controls subsequent modes of knowledge production through codifying

differences between the civilised West and the underdeveloped Rest.

Prestø further explained that, “What that means is that we started

to change education. We start to change storytelling. We started to

fabricate our view of ourselves and the view of the rest, so-called

othering. […] So, we are civilised, we are highly cultured, but they

are dumb and savages. Therefore, we must dominate them. We must take

their land. we must take their women.”

Below is a list that Prestø created to highlight which words are

hiding the brutal truth:

Colony = invaded country

Colonialisation = war

Slaves = hostages

Slave owners = human traffickers

Slave catchers = police

Plantation = death camps

Mistresses = rape victims

Overseers = torturers

Trading = kidnappers

Profit = theft

He then rewrote a passage that initially read, “Slave families lived

on plantations owned by white slaveowners who hired overseers to

maintain discipline,” to “Black families were held hostage in death

camps by white human traffickers who employed torturers to torture

and kill them.”

“We need to start there, to understand how much we are hiding in our

everyday talk.” The recent ‘blackface’ debate in Norway was an

example of how Norwegians were ridiculing “blacks at death camps”,

and he called the discussion “dumb”, “absurd”, and “undignifying”.

Academic accountability: Shifting the Geography of Reason

“If you don’t apply decolonial perspectives in your research on

Africana Dance you will reach less than 60 years back in time, and

most of what you glean will be “corrupted” information,” warned

Prestø.

The origin of the concept of “shifting the geography of reason” was

born out of a dialogue between the Department of Africana Studies at

Brown University, the Institute for Caribbean Thought in Jamaica,

and the Africana Thought series at Routledge in the late 1990s on

the decolonial thought movement. It is also the motto of the

Caribbean Philosophical Association.

Shifting the geography of reason is to change the historical

perpetuation that Africans are non-intellectuals, and thus were

denied the capacity to produce knowledge and to have rational

thought. When such bias, especially in the context of Western

philosophy, is so prevalent it has dire consequences for our society

and education.

“Euro-Western believes that they own reason. Therefore, this

pertains in art,” said Prestø. Speeding through he highlighted how

the map of Africa is unnaturally constructed and distorted in the

commonly used Mercator’s world map in classrooms, where Africa is in

fact much larger. Africa as a continent has its own diverse cultures

and had kingdoms with their own trade, libraries and universities in

pre-colonial times.

Prestø used examples of “Fulani” languages and “Bantu” culture to

illustrate African diversity. Fulani language group is from the

Niger-Congo family, with its dialects being are spoken across 22

countries in West and Central Africa. It is also spoken from Senegal

and in Sudan too. There are about 20-30 million Fulani speakers

across Africa. Despite their dialects, for Prestø, they are all part

of the same “rhythmic culture” and can communicate with each other.

African drums, also known as talking drums, were outlawed in the

colonies because of their ability for the enslaved to communicate.

The importance of understanding cultural structures, in particular,

is to get the right solutions for example working with African

youth, “Rather than trying to assimilate somebody for drug

prevention, you can actually look at what you have in your own

culture that could work as drug prevention and start there. It’s a

lot easier.” Prestø worked with African youth in Norway.

Rhythm is Communication. Time is Relational.

The main philosophy in most parts of Africa is polycentricity, where

everyone is important and can influence in the same space. This has

a consequence in art. Polyrhythm comes from polycentricity.

Polyrhythm is multilayers of voices, which Prestø described in a

social context, African aunts talking at the same time where one

aunt can be talking about two different things. It does not mean

that in that space one aunt can be bigger than the other or louder

than the other, but rather the other aunt would also need to be

bigger and louder as well. The idea of “your turn to speak after my

turn to speak” does not resonate in the African culture.

Individuality is then seen as being established and found in a

group, and “Difference does not communicate less value.” Ubuntu, is

an ancient African word and philosophical concept to mean “I am

because we are” which underpinned African culture.

Rhythm is to be understood as a core way of communication. Most of

the dances and songs are based on cosmology, which is why he titled

his lecture as ‘Assuming the Centrality of an Africana Cosmos –

Beyond Coloniality.’ Dance is then seen as a way to communicate to

the universe and is considered as “the highest form of

communication.”

Skills in listening, creation and tracing is important to master the

rhythms in African dance, and once again he emphasised that the

euro-western notation system in music is not “capable of notating

polyrhythms correctly.”

When talking about the dancer’s body, Thomas refused to use the

term, ‘black bodies’ as this is where you are only black in the

presence of whiteness. “If you let the whiteness become the norm, so

that you have to define you are black, it’s like saying black South

Africans. Why do you have to say that? It is because of the force in

the room.”

In the African perspective, the human body is seen as so exquisite

that even the gods want it. In a voodoo ritual dance, an exchange

occurs when the divine spirit enters and rides the body; for lending

the body, the spirit leaves healing and knowledge to the community.

Rhythm is also seen as the making of time. Prestø raised the

question of how and who defined time itself, “Who says that the half

time of an atom in Geneva dictates what a second is? […] How long is

an hour? Let’s say from an experimental point of view. It could feel

like five minutes. Hours can feel like a week. Now with corona, who

knows what day it is?”

“Time is relational, so are polyrhythms. It teaches us how to stand

in time, and it also teaches us not to try and control it. It

collapses time. So, the drum often teaches us who we were, who we

are, and who we can become. It takes three spirits to beat the drum

– the ancestral tree, that was taken to make the wood; the animal

that was sacrificed to make the skin, and the human who beats it in

the moment. Past, Present and Future have to be present for the drum

to sound.”

Thomas Talawa Prestø is the founder and art director of Tabanka

African and Caribbean Peoples Dance Ensemble, which has won awards,

such as OXLO-prisen 2017 and Bergesenprisen 2020.

This article is part of a journal series produced by The Oslo Desk in collaboration with Oslo Afro Arts Festival.